Delta-X studies how land is lost and gained in river deltas.

Why deltas?

River deltas build land where a river reaches a shallow coast and deposits large amounts of materials. The water carries a lot of sediment (silt, gravel, clay, etc) down the river, building up land where it meets the ocean, creating a river delta.

More than half a billion people live along the coast, including river deltas. These coastal marine environments contain many resources that people and animals rely on:

Provide food supply with nurseries for fish, crustaceans, and mammals

Provide food supply with nurseries for fish, crustaceans, and mammals

Have rich soil, where plants flourish. This vegetation takes carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air

Have rich soil, where plants flourish. This vegetation takes carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air

Sustain a health, biodiverse ecosystem

Sustain a health, biodiverse ecosystem

Provide safety, blunting the force of winds to protect communities and infrastructure

Provide safety, blunting the force of winds to protect communities and infrastructure

What's happening to deltas?

Deltas are sinking. All large deltas are in peril or on the verge. They cannot grow fast enough to offset sea level rise and subsidence (sinking) of land.

Why does land subside (sink)?

Land sinking is mostly caused by human activities, including mining and extracting underground fluids, such as petroleum, natural gas, or groundwater.

This image shows the location of the maximum subsidence in the United States: San Joaquin Valley, California. The dates on the pole show the altitudes of the land surface at those years.

Deltas are the babies of the geological timescale. They are very young and fragile, in a delicate balance of sinking and growing.

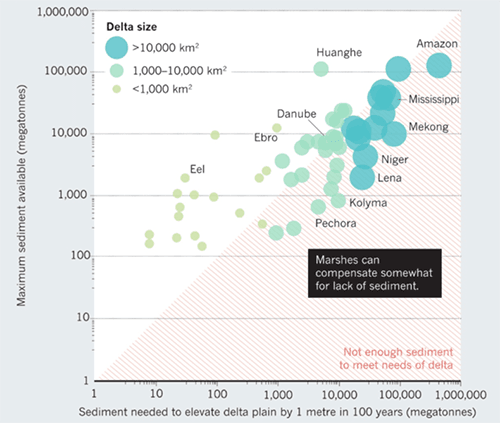

Most of the large deltas (large circles) are sediment-starved, they are not building soil fast enough to keep up with sea-level rise.

Why does sea level rise?

For two main reasons, both caused by global warming:

- Thermal expansion: when water heats up, it expands, and the water simply occupies more volume.

- Melting glaciers: higher temperatures cause more melting in the summer, and less snowfall due to later winters and earlier springs.

What can we do about it?

To combat the sinking, deltas need to build land. There are two ways to do this:

- Capture soil that came from somewhere else, typically up-river

- Build the soil locally through vegetation growth

How can vegetation both help and hurt land building?

If the water moves too fast, then the soil won’t stay. Vegetation can help slow down that water, so it can capture more soil.

But if the vegetation is too thick, then it stops the water, causing sinking until the land is inundated and lost.

Why the Mississippi River Delta?

The Delta-X mission studies the Mississippi River Delta, the most famous river delta in the United States and the 7th largest river delta on Earth.

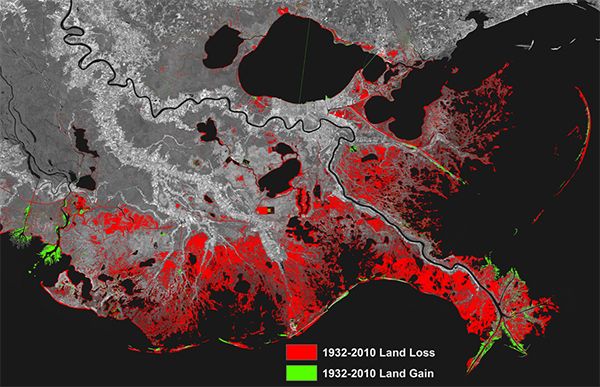

Millions of people live on the Mississippi Delta, along with a unique ecosystem of plants and animals. On average, one football field of land is lost per hour.

- It has land loss adjacent to land gain. So in one area, we can study how land is built and how land is lost.

- This area experiences some of the largest sea-level rise in the world, at 9–12mm per year. This land loss is happening to deltas all over the world, but it is happening faster here, and people are trying to prevent it.

- What is happening here will soon be the standard conditions—if not already—in most other deltas.

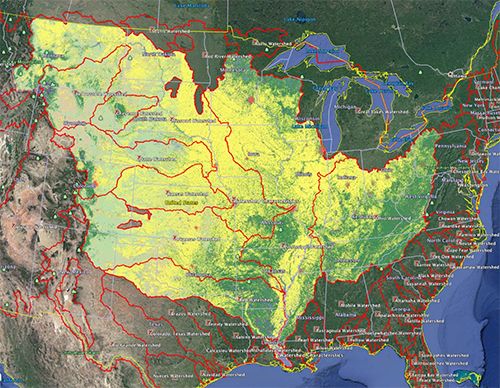

The Mississippi Delta watershed extends over 40% of the contiguous United States. All the water that falls in this area drains into the delta, 200–300 million tons of sediments per year flowing to the ocean.

The main study site is the Atchafalaya Basin, chosen for its diversity of plant structure, and because parts of it are losing land at the fastest pace in the whole delta, but other parts are growing, gaining land.

So what makes one area grow and another a short distance away disappear? If we knew that, we could devise plans to change the decline. This is the perfect place to study what drives that difference.

The Mission

To understand how the Mississippi River Delta is growing and sinking, the Delta-X mission uses airborne (remote sensing) and field (in situ) measurements to look at the water, vegetation, and sediment (soil).

Sea Grant is an applications and outreach partner of Delta-X.

Water

AirSWOT (Air Surface Water and Ocean Topography): the Ka-band radar measures water slopes (elevation change) in the big channels.

UAVSAR (Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar): the L-band radar measures the network of small channels that carry water into the wetlands, water level changes, and how that water changes over time in areas of vegetation.

Field measurements: includes water level, bathymetry, water velocity.

Vegetation

AVIRIS-NG (Airborne Visible / Infrared Imaging Spectrometer): the spectrometer classifies the vegetation.

Field measurements: includes mapping vegetation types, biomass.

Sediment (soil)

AVIRIS-NG (Airborne Visible / Infrared Imaging Spectrometer): the spectrometer looks at the color of the water, which indicates different amounts of sediment.

Field measurements: using feldspar to measure how much soil has accumulated recently, and soil cores to look at how soil has accumulated historically.

After the data collection, all the measurements are brought together to calibrate a model, which scientists can use to:- Predict how the Mississippi River Delta will likely respond to rising sea levels in the next 100 years.

- Identify areas that are vulnerable to sea level rise and storms.

- Understand and forecast land gain or loss in deltas.

Putting the data together gives information that could not be gotten without all of the sensors taken together.

Delta-X is studying why land is lost and why it is gained, so we can help make deltas grow. This delta model can then be applied to many places around the world, giving us a glimpse of the future of all deltas.

Delta-X in the Field

Marc Simard, Delta-X principal investigator (PI), heads to the Mississippi River Delta and collects measurements with the science team. This was during the 2016 Pre-Delta-X demonstration campaign.